My name is Salwa Rita Mourtada Bamba. I am originally from Liberia in West Africa, and I came to the United States seeking asylum when I was 20 years old.

Before the civil war, life in Liberia was everything a kid would hope for. I had two brothers and my older sister. We grew up together on a huge property where my father had a couple of stores and a restaurant. There were gazebos and tables all over the compound, a basketball court, volleyball court, and a playground with swings, merry-go-round, seesaw, monkey bars. It was a kid’s dream.

But when the war started in 1989, everything changed.

I was 12 when the country started to get tense. We could tell something was wrong, and we would see footage on TV of the massacres. We watched the rebels advance toward the capital and as they approached our area, we saw the fires, the looting, the rape. My father was captured and we didn’t see him for a long time. It was just me, my siblings and my mom in a camp. Everything was destroyed. We were sleeping on the floor. We had nothing.

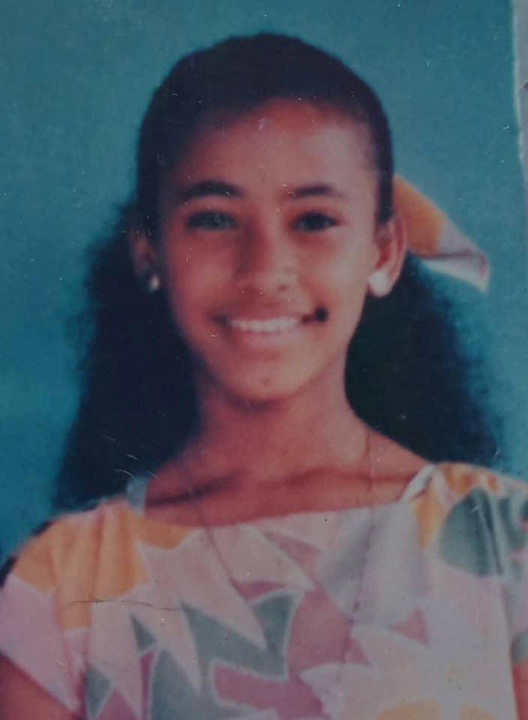

We were reunited with my father in 1991, but not long after that, my sister Laila Annette was captured and murdered. Believe it or not, our family never sat down to talk about her death. I don’t think any of us have the courage to reminisce about her life because we’re afraid to break down. She had so many dreams. She would say, “I want to be an artist. I want to be a surgeon. I want to be a firefighter.”

After Laila’s death, my parents sent me to Ghana to stay with an acquaintance from church, who provided a place to live, but no other support. It was so difficult not having parents with me as a 14-year-old. When I got sick with typhoid fever, I had no one to take care of me. I would go to the hospital and there was no one to pay the bill.

After I graduated from high school in Ghana, I started to dream about studying medicine in the United States. I had become interested in medicine during a period of relative peace in Liberia, when I helped United Nations doctors care for the sick and injured as a 13-year-old triage nurse. It brought me so much fulfillment to watch people get better. And I had always dreamed about America. In Liberia, all of our school books were from America, so I knew about Pecos Bill and tornados. At my dad’s restaurant, I would change my accent to speak like an American.

My dad had connections, so when I told him about my dream of studying in the United States, he talked to the American ambassador for me. Eventually, when I was 20, I came to New York City by myself. Reality hit me when I arrived at my aunt’s place in Queens and I saw that she had six children in a two-bedroom apartment. I started missing my nice beach back home.

After a year in New York City, I moved to Colorado, where my uncle lived, and I started pursuing a bachelor’s degree in nursing at CU Denver. Because of my temporary protected status, I was never eligible for federal or state aid, which meant I had to work for one semester to save up money, go to class for a semester, and then stop to save up money again. To add to the challenge, my temporary protected status would expire every 18 months, along with my driver’s license and my ability to work. That’s when I really had to hustle.

Later, when I had children, we relied on food stamps and food pantries. At one point, I was homeless and slept in my car with my son. Before one particular semester, I begged the bursar to let me register even though I didn’t have the money to cover the fees. He suggested I apply for scholarships. I said, “I don’t have a green card. I’m not eligible.” He replied, “You might find one or two that don’t have those requirements.” So, I looked and finally found one for $2,500. I applied, and lo and behold, I got it. From then on, I would always enter to win some award, and I would receive $1,500 here and there.

I also got help from people who knew what I was made of. My pastor loaned me $3,000 to pay for my first semester at CU. My brother loaned me a few hundred dollars here and there. When my dad was alive, he would send me money. And a few years ago, my mom loaned me $5,000 to pay for a semester of my master’s program. People have stood by me and pushed me. I stand on their shoulders today and I am proud.

My life changed when I graduated with my bachelor’s degree and got my nursing license. I moved out of my little condo where the landlord was after me every week and rented a beautiful apartment. Fifteen years after I arrived in America, I finally found my feet.

While I was working on my bachelor’s degree, I was always driving up and down Colfax Avenue. I watched the Fitzsimons campus being transformed into the Anschutz Medical Campus and I said to myself, “I will graduate from here one day.”

True to my word, I did graduate from the University of Colorado College of Nursing in 2020, and I currently work there as an assistant professor and at the CU Family Health Clinic as a nurse practitioner. I love my job. When I learn that a patient has done something I told them to do, I yell, “Oh my god!” and everyone comes running, thinking something’s wrong. But I’m just celebrating that my patient is doing OK. The saying is true: Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.

The benevolence of others has been crucial to the story of my success. I cannot overemphasize how their willingness to help and be of service has impacted my life and my children. My daughter and son are both scholarship recipients at CU Boulder, and my son is about to complete his engineering degree with scholarship support from the Engineering GoldShirt Program.

Sometimes I wish my journey would not have been so rough. But despite everything, I am blessed. Everything that happened along the way has prepared me for what I will be called to do tomorrow.

With scholarship support, Salwa Bamba graduated with three degrees from CU: a bachelor’s degree in nursing in 2011, a master’s degree in nursing in May 2020, and doctor of nursing practice degree in 2021. She joined the first nurse practitioner fellowship in geriatric medicine at the UCHealth Senior’s Clinic, and she serves as a board member of the CU College of Nursing Alumni Association and the Community College of Denver Business Administration Advisory Board.

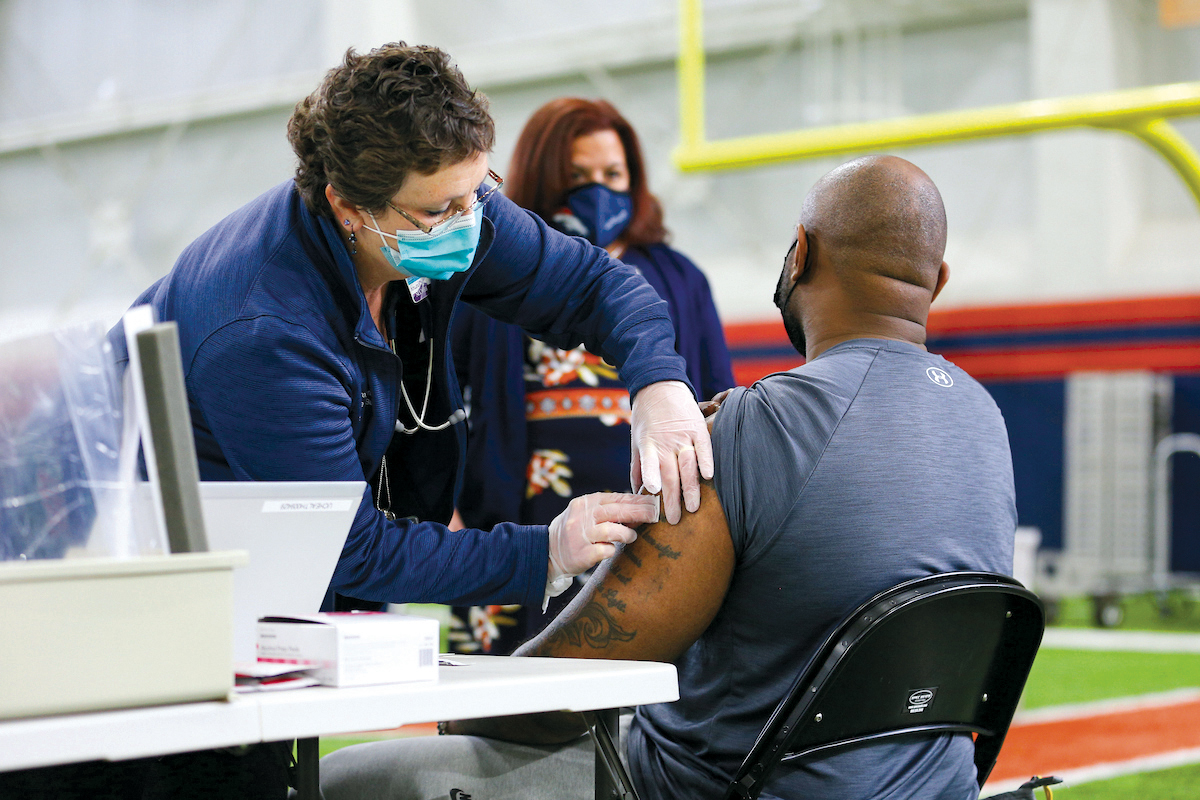

Bamba is currently a clinical faculty member at the CU College of Nursing’s Belleview Point Clinic, a facility for patients from marginalized backgrounds. She also mentors high school students through Denver Public Schools and has worked with the Cherry Creek School District to host immunization drives for low-income students and families. As a student at the CU College of Nursing, Bamba and a group of classmates started Future Voices, an organization striving to amplify the voices of underrepresented nursing students. The group currently runs a mentorship program with Hinckley High School, hosts donation drives for books and scrubs, and fundraises to help nursing students pay for school. Bamba also runs the Laila A. Mourtada Foundation; named after Bamba’s sister, the foundation focuses on education and health literacy for women and girls in Liberia.