Why not be fearless when fighting a global pandemic?

CU Anschutz's Dr. Michelle Barron battles the COVID-19 pandemic on the front lines and keeps smiling despite the challenges.

Why not be fearless when fighting a global pandemic?

CU Anschutz's Dr. Michelle Barron battles the COVID-19 pandemic on the front lines and keeps smiling despite the challenges.

Dr. Michelle Barron has had a tough three years. When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency in the U.S. in March 2020, her job put her on the front lines.

But Barron, the senior medical director of infection prevention and control for UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital, and her team were up for the challenge, drawing on years of experience researching infectious diseases to improve public health outcomes.

Our team approaches every day asking ourselves, ‘Why not aim for zero preventable infections?’ Then we build systems and operations to make that a reality.

-- Dr. Michelle Barron

“Fear of the unknown doesn’t scare me at all because this is what I do. I’m an infectious disease doctor and I do detective work,” Barron says. “I often start with unknowns and that's what drives me to try and figure out what is wrong.”

Responding to the Unknown Without Fear

As an expert on infectious diseases, Barron’s job involves planning for pandemics before they happen.

“People don’t think about this, but pandemics occur about every 10 years. They’re not all of the same magnitude, but if you’re in my world, you prepare,” Barron says. “You think through what resources you need for patients and for staff.”

So, when COVID-19 hit in March 2020, Barron and her staff were able to take a systematic approach to understanding the pandemic even though there were so many unknowns.

“We were dealing with a new disease. In addition to a lack of information, there was also an unbelievable amount of erroneous information. The evidence wasn’t as firm as we were used to, everything was changing quickly,” she says. “It was like working in a hurricane.”

Dr. Michelle Barron at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital.

To develop an effective pandemic response, Barron and her team drew on existing models from the 1918 flu pandemic and other pandemics to predict disease spread, to plan for staffing shortages and hospital triage measures and to determine how to prevent transmission.

“While I can appreciate that some things are not preventable, our team approaches every day asking ourselves, ‘Why not aim for zero preventable infections?’” Barron says. “Then we build systems and operations to make that a reality.”

With these models, they were able to plan for hospital staff and their family members getting sick which enabled them to backfill positions and plan for staff to miss work due to their children’s school closures.

Inspiring Patients and Donors

Barron's can-do attitude has drawn attention from donors over the years.

After a rare bacterial infection landed George Sissel in the hospital in 2019, he and his wife Mary Sissel were so impressed by Barron’s approach to diagnosis that they decided to support her research.

Barron says their generous offer came at a particularly crucial time for her.

“I had been wanting to look at how many people get fungal infections,” she recalls. “It’s an important area of study but it’s not something you get federal grants for. When I met the Sissels, I had just been getting to the point where I was about to say I’m not doing research anymore.”

With help from the Sissel family, Barron’s research got back on track. Barron has since partnered with her colleague, Dr. Esther Benamu, to complete a study on fungal infections in patients with underlying blood cancers or transplants. Barron is also investigating the links between COVID-19 and fungal infections.

Working with Communities

In addition to providing patient care, conducting research and steering the hospital through its pandemic response, Barron also partners with churches, community centers and other local organizations on community outreach. Barron’s team leverages the organizations’ community connections to reach the largest number of people.

“Often, the natural cultural navigators will be community members with a bit of health care training that people seek out when they need something,” she says. “Once you find them, you sit down with them and get them on board. That’s how you reach the rest of the community.”

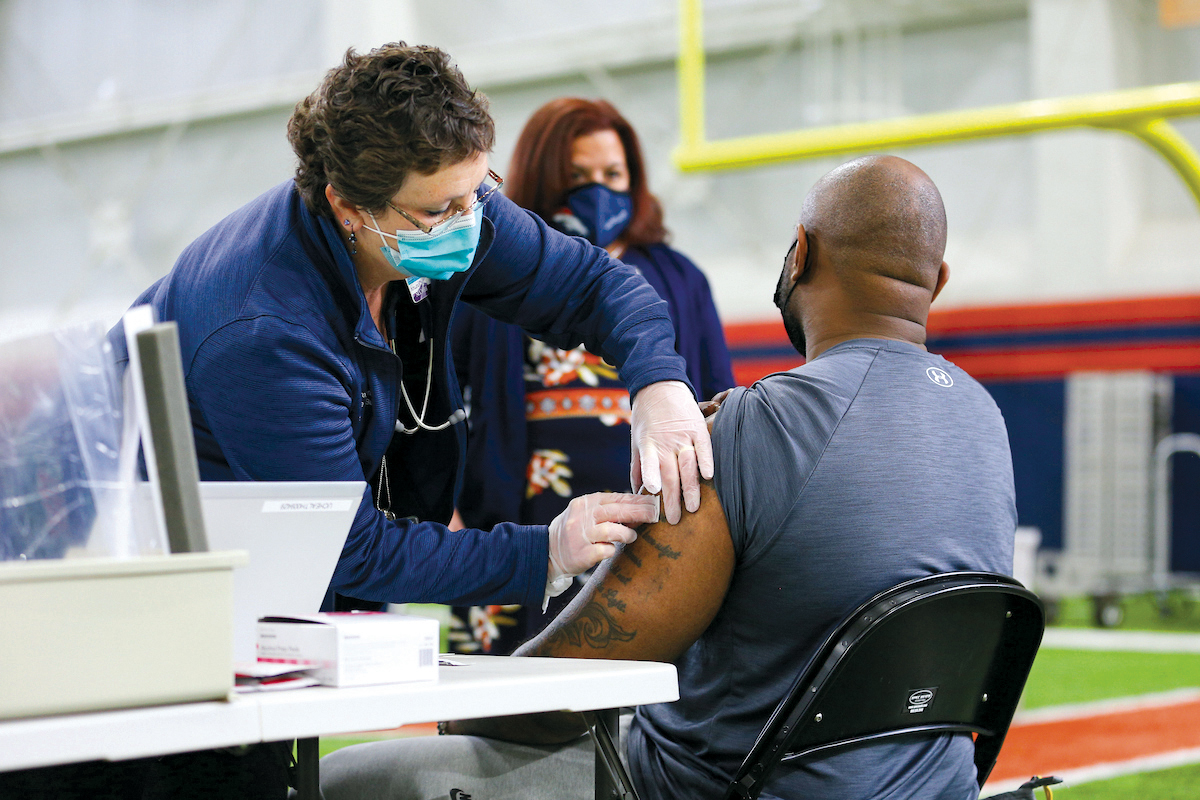

Barron also made it a priority to support public COVID-19 vaccination drives throughout Colorado. At one vaccine drive held next to a Broncos training camp, Barron spoke with local news reporters who were on site to cover the training camp.

“People actually showed up and said, ‘We saw you on the news just now and thought, well, why not?’” Barron recalls. “That was one of my heart-melting moments where I was so happy I do this work. If I can convince one person to get a vaccine, I’ve made a difference in the world and that matters to me.”

Barron (in background) oversees vaccination event for the Denver

Although Barron says she was never afraid during the pandemic, her anxiety level would rise and fall based on what was happening. She struggled with “turning off” after long and stressful days, but personal support from friends like the Sissels sustained her through the toughest times. “Like many of my friends did throughout the pandemic, Mary and George would text me if they saw me on the news or on a campus presentation to wish me well,” Barron says. “Their philanthropy is an example of how they watched and cared for me, but they also did this in a very personal way.”

Sean, a citizen of three different countries, master of two languages and relisher of a pint of Guinness.

Sean, a citizen of three different countries, master of two languages and relisher of a pint of Guinness.

Nina Jean was a rancher’s daughter, who passed down the value of working hard and helping others. She was the kind of grandmother who let you pick out whatever sugary cereal you wanted in the grocery store and who baked an extra pumpkin pie at Thanksgiving so you could eat it for breakfast the next morning.

Nina Jean was a rancher’s daughter, who passed down the value of working hard and helping others. She was the kind of grandmother who let you pick out whatever sugary cereal you wanted in the grocery store and who baked an extra pumpkin pie at Thanksgiving so you could eat it for breakfast the next morning.