At UCCS, ‘unstoppable’ women scholars shed obstacles, commit to success

Tiffany Sinclair’s journey took some unexpected turns.

She endured the sudden death of her husband from toxic shock syndrome, the diagnosis of her 11-year-old daughter with brain cancer, then the death of her mother from liver cancer.

So when Tiffany was notified several years back that the University of Colorado Colorado Springs had accepted her as a Karen Possehl Women’s Endowment (KPWE) scholar, she remembered being shocked.

“I thought, ‘Wow. Somebody heard my story,’” she said. “It was really the inspiration for me to keep going.”

Which she did, all the way to the master’s in counseling and human services she earned in 2015.

Each year at UCCS’ KPWE Unstoppable Women’s Luncheon, more than 400 people gather to hear stories like Tiffany’s, shed tears of joy and share looks of amazement.

Then, they make gifts to support more UCCS scholars who have overcome formidable personal obstacles to their college education.

Just a few of the challenges KPWE scholars have overcome include spousal abuse, substance addiction and family health crises.

Such challenges are extreme even compared with other nontraditional UCCS students—and nationally, only about one in three “typical” nontraditional students graduate. But with the program’s tuition support (more than $350,000 in 20 years), personal mentorship, and childcare support, KPWE scholars have a 93 percent graduation rate.

The Unstoppable Women’s Luncheon is annually a red-letter date not only for UCCS, but also for Colorado Springs civic and community leaders who often double as KPWE mentors. One such leader is local arts luminary Mary Mashburn.

“Every year, I wear the same jacket to this event, and I contribute what I don’t spend on a new jacket for this event as a donation to KPWE,” Mary told the crowd in 2015, her ninth year at the luncheon.

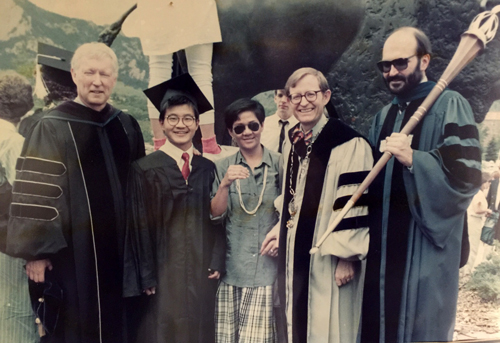

Tandean was an undergraduate business student from Indonesia and the first in his family to get a college education. His working-class parents, with only middle-school educations, helped pay for it by selling their house back in their village. He worked three jobs in Boulder—one of them washing pots and pans in Nichols Hall for $3.25 an hour—and only got haircuts twice a year. He borrowed money from his college roommate to pay his last tuition bill. But he felt lucky to have the American college experience, rooting for the Colorado Buffs football team and going to the popular college bar Tulagi with friends.

Tandean was an undergraduate business student from Indonesia and the first in his family to get a college education. His working-class parents, with only middle-school educations, helped pay for it by selling their house back in their village. He worked three jobs in Boulder—one of them washing pots and pans in Nichols Hall for $3.25 an hour—and only got haircuts twice a year. He borrowed money from his college roommate to pay his last tuition bill. But he felt lucky to have the American college experience, rooting for the Colorado Buffs football team and going to the popular college bar Tulagi with friends.